Many reef hobbyists, myself included, may have had their first foray at coral husbandry courtesy of a corallimorph. These so-called “mushroom-corals” of the taxonomic order Corallimorpharia are not true stony corals phylogenetically, but instead, represent a sort of “missing link” between sea anemones (order Actiniaria) and stony corals (order Scleractinia).

Corallimorphs went mostly unnoticed by the scientific community until the 1940s. Early taxonomists grouped these with carpet anemones of the genus Stichodactyla due to a superficial similarity regarding the number and arrangement of tentacles associated with each internal mesentery. However, after more careful study, it was found that corallimorphs lack the basilar muscles found in all true sea anemones. This prevents corallimorphs from moving in the same creeping fashion that many sea anemones utilize (if you’ve ever watched a bubble-tip anemone move, you know exactly what I’m referring to).

Other muscles that are considered to be unifying traits of sea anemones like the sphincters and retractor muscles are also poorly developed or completely absent in corallimorph taxa. Additionally, corallimorphs differ from sea anemones on a microscopic level, specifically in the morphology of their stinging cells.

Discounting a surface-level resemblance to their sea anemone cousins, corallimorphs are more closely related to scleractinians and are essentially stony corals without calcium carbonate skeletons. One of the most notable similarities is the presence of large nematocysts (stinging cells). In tentaculate corallimorphs like Corynactis or Pseudocorynactis, these stinging cells are aggregated on globular structures called acropsheres located at the tips of their tentacles. These similarities have led scientists to believe that corallimorphs evolved directly from stony corals around the time of Permian Extinction when ocean conditions inhibited the deposition of calcium-based skeletons, a concept known as the “Naked Coral Hypothesis”.

Despite a decent degree of diversity in our oceans, “desirable” corallimorphs in the reef aquarium hobby generally come from one of three genera: Discosoma, Rhodactis, or Ricordea – the latter two of which we will save for future articles.

Discosoma is a genus of flattened, zooxanthellate corallimorphs that lack peripheral tentacles and are named for their disc-like appearance. The genus stems from the Greek words for disk and body – “diskos” and “soma” respectively. Discosoma can be found in warm waters throughout much of the Indo-Pacific, Caribbean, and tropical West Atlantic.

In many regions, Discosoma can be found in the intertidal zone but many species occupy sheltered reef habitats at conventional SCUBA depths. However, despite their expansive range in relation to both their biogeography and depth distribution, the genus Discosoma likely consists of less than a half dozen species based on emerging genetic data.

Discosoma nummiforme

By far the most commonly seen species of Discosoma in the reef aquarium hobby is Discosoma nummiforme. This species also has the broadest distribution of any species within its genus. D. nummiforme is found throughout the Indo-Pacific and into the Red Sea. This species is rather variable in appearance but can generally be identified by having discal tentacles that are either extremely reduced or completely absent. Below is my entirely unscientific attempt to categorize some of the diversity of phenotypes in this species based on shared traits.

Many of the most common aquarium varieties of Discosoma belong to this species. The nondescript red and blue Discosoma that tend to take over the rockwork in every tank they’re introduced to are a classic example. These tend to have somewhat subdued monochromatic coloration relative to their conspecifics with irregular discal tentacles scattered across their oral disk. However, some aquarium specimens exhibit much more dazzling colors while still maintaining the same general morphological details.

Another common variant of D. nummiforme have oral disks completely or almost completely devoid of discal tentacles. The surface of these polyps exhibit varying levels of texture depending on the particular phenotype in question, but all collectively exhibit an outward appearance of “smoothness” relative to their conspecifics. Morphs like those by the names of “Ironman” and “Pinwheel” are what I could consider to fall into this category.

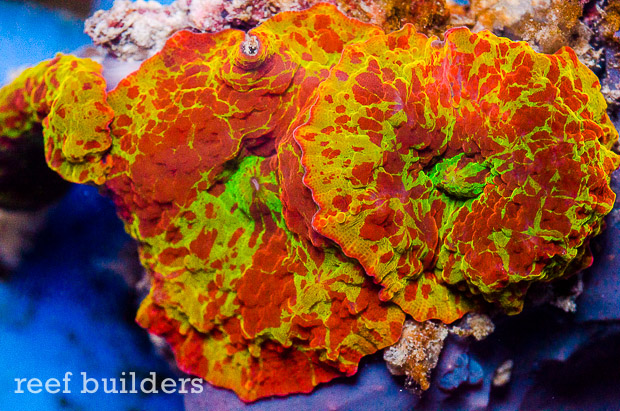

Another common variant of D. nummiforme possess enlarged, hemispherically-shaped discal tentacles. While the size of these tentacles can vary from mushroom to mushroom, within the same polyp they tend to all be of similar size and arranged in rows radiating outward from the mouth. Coloration is incredibly varied with a morph existing for practically every color combination imaginable. However, what does seem to be consistent is that the polyps are bicolored, with discal tentacles contrasting with the coloration of the oral disk. “Leopard” and “Superman” Discosoma are popular examples of this group.

Less common is a variant with radially oriented vesicles that rise above the rest of the oral disk. These polyps vary greatly in color and discal tentacle properties. In my headcanon, these are just examples of the aforementioned three groups but have developed characteristically inflated vesicles on their oral disk. These vesicles probably form through a similar pathway as the more balloon-like vesicles in “bounce mushrooms”. It is also likely that any Discosoma can develop these structures, but not all do.

Discosoma dawydoffi

Discosoma dawydoffi is a somewhat uncommon species found throughout the West Pacific. Polyps of this species are fairly distinctive, with enlarged discal tentacles organized in rows corresponding to higher-order mesenteries. These “pimply” discal tentacles are almost globular in shape rather than the hemispherical ones of D. nummiforme. Additionally, the column is shorter than that of D. nummiforme so the polyps of D. dawydoffi lie flat against the substrate.

Additionally, unlike D. nummiforme, the color palette of D. dawydoffi is fairly limited, with polyps almost always taking upon some combination of green, turquoise, and purple hues. In some specimens, the enlarged discal tentacles may have a sparkly appearance due to some underlying iridescent quality of the structure’s tissue or mesoglea. The only variant of D. dawydoffi that I have ever seen in the reef aquarium hobby is commonly referred to as a “Lava Lamp” Discosoma, likely on account of its large bubbly discal tentacles.

Discosoma neglecta

Two members of the Discosoma genus are endemic to the Caribbean and tropical Western Atlantic – D. neglecta and D. carlgreni. The first species, Discosoma neglecta, is easily recognized by the presence of lobes on the margins of its oral disk. These lobes are thinner than the rest of the polyp but vary greatly in size and shape with larger lobes often alternating with much smaller lobes along the polyp’s perimeter. These lobes should not be confused with the marginal tentacles present in other corallimorpharian genera like Rhodactis.

The discal tentacles in D. neglecta tend to be highly reduced and arranged radially across the surface of the oral disk. These can be hemispherical or irregularly shaped with secondary protuberances giving the larger tentacles a degree of branched complexity. Smaller discal tentacles may be harder to notice but often resemble minute flap-like projections.

Discosoma neglecta polyps are wide and convex when fully extended, which is where their infrequently used common name of “umbrella mushrooms” originates. However, while the polyps of many Discosoma species contort during retraction, Discosoma neglecta adopts a rounded concave shape, reminiscent of a shallow bowl. The majority of individuals from this species are a subdued green, turquoise, or tan color, but prized aquarium specimens display breathtaking polychromatic hues, often with iridescent qualities.

This species is fairly widespread throughout the Caribbean, but not particularly abundant in any one region. Typically it can be found solitarily or in loose aggregations of a few clonal individuals in shallow waters between 5 – 20 meters of depth. D. neglecta seems to prefer shaded microhabitats and is commonly observed under small overhangs and rock crevices. Asexual reproduction in this species occurs via pedal laceration and longitudinal fission has never been observed in this species.

Discosoma carlgreni

The other Discosoma species found in Caribbean and Western Atlantic waters is Discosoma carlgreni. This is a more obscure species that has a broader distribution than its congener D. neglecta, being found as far north as Bermuda and as far south as Brazil. However, despite being found across a greater stretch of ocean, it seems to be less frequently observed in-situ than D. neglecta. When it is seen in the wild, it typically occurs in very shallow waters (sometimes intertidally) among turf-forming algae. Like most corallimorphs, Discosoma carlgreni seems to prefer sheltered microhabitats, settling among divots and crevices in the substrate.

This species may have a smooth outer margin, but more typically has tissue drawn outward into blunt or triangular projections. Unlike most of its congeners, Discosoma carlgreni may also exhibit marginal tentacles, although perhaps infrequently. These marginal tentacles may even have acrospheres like those in Rhodactis, which the polyps use in spatial competition against other corallimorphs and sessile reef fauna.

Discosoma carlgreni is by far the least frequently encountered species of Discosoma in the reef aquarium trade. When it is offered for sale, it is sometimes mislabeled as a Rhodactis, which it can closely resemble at a glance. Many vendors also misidentify this species as Discosoma neglecta. Occasionally the inverse is seen as well, with D. neglecta sold as D. carlgreni, but the former is more common. Polyps of this species typically exhibit shades of blue, green, and brown. More colorful varieties do occasionally enter circulation but are quite uncommon.

The validity of both D. carlgreni and D. neglecta as distinct species remains up for debate. Both have lobed oral disk margins, can develop relatively complex discal tentacles, and share similar color patterns. However given their disparity in habitat and depth distribution, it could be that they are ecomorphs of the same species rather than two distinct species. Ultimately, proper molecular sequencing data is needed to draw any further conclusions.

Platyzoanthus / Discosoma mussoides

The corallimorph currently accepted as Platyzoanthus mussoides presents an interesting taxonomic situation. This species was originally described from the Torres Strait (a small stretch of water in the Great Barrier Reef between Queensland, Australia, and the island of Papua New Guinea) in 1893 by a controversial English marine biologist named William Saville-Kent. For decades the genus Platyzoanthus has been considered monotypic, bearing a single species, P. mussoides. In some sources, this species may also be listed as “Rhodactis mussoides” but those references are either outdated, misidentifying this species, or both.

The morphology and biology of Platyzoanthus mussoides are unique amongst corallimorphs, likely contributing to its placement within a monotypic genus. Individual polyps of this species are quite large ( reaching 5 inches across) and covered in a network of intricate ridge-like protrusions, giving them a heavily textured appearance. Additionally, these polyps are generally polystomatous, meaning that each one can develop multiple mouths. P. mussoides is also the only corallimorph that undergoes asexual reproduction via incomplete longitudinal fission.

In many cases, asexually reproducing polyps will not completely divide, but remain attached to the mother polyp. This results in a technically colonial corallimorph composed of several conjoined individuals that can reach over a foot across. Clonal aggregations of these “super-polyps” can cover large expanses of reef, particularly in shallow, protected waters.

Most specimens of P. mussoides are a drab tan color but aquarium specimens sometimes adopt a vibrant green or yellow color depending on their genetics. These are typically sold under the name of “elephant ear mushroom corals” – not to be confused with another large corallimorph species, Amplexidiscus fenestrafer. Some have reported that these exceptionally large corallimorphs are notorious for consuming fish and invertebrates. However, it is unclear whether these polyps are physically capturing their prey or just consuming dying organisms.

Recent genetic evidence has found that P. mussoides fits well within the Discosoma genus and forms a well-supported clade with at least two Discosoma species. However, at the time of writing, many taxonomic databases still list this species under the genus Platyzoanthus, despite mounting evidence against that classification and growing support by anthozoan taxonomists for its reclassification.

St. Thomas Mushrooms

The corallimorph known as the “St. Thomas Mushroom” has historically been identified in the reef aquarium hobby as Discosoma sanctithomae. This reflects the Caribbean island of St. Thomas from which its colloquial namesake stems. Unfortunately, taxonomy rarely yields for the sake of convenience, and the name “Discosoma sanctithomae” has been defunct since 2016. At the time of writing, current taxonomic standards maintain that the St. Thomas Mushroom is a species of Rhodactis called R. osculifera. Upon closer inspection, this classification makes sense as St. Thomas Mushrooms have marginal tentacles lining the periphery of their oral disk much like other species of Rhodactis.